The Air Force May Ditch GPS for Earth’s Magnetic Field

- The Air Force, wary of losing its GPS satellites during a major war, is exploring alternatives.

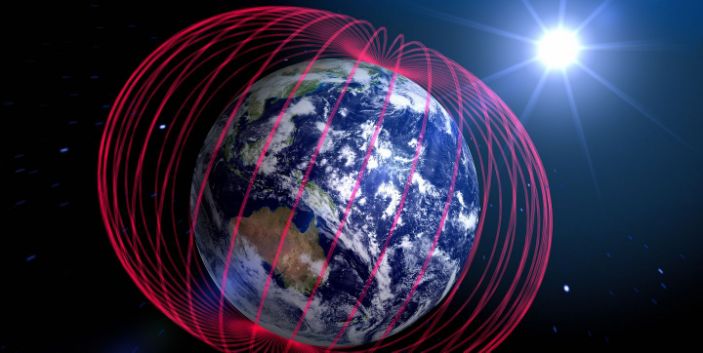

- One alternative is using a magnetic field map of Earth.

- Maps of Earth’s magnetic field are very accurate, but we don’t know how data is gained about possible enemy territory.

The U.S. Air Force, concerned that adversaries might target its fleet of GPS satellites in wartime, is looking into Earth’s magnetic field as an alternative, according to Defense One.Accurate and extremely difficult to jam, the magnetic field could be used as a means of navigation for ground troops, ships at sea, and aircraft. The magnetic field could also guide missiles to their targets with an accuracy of just over 30 feet.

The worldwide Global Positioning System (GPS), created in the late 1980s, has evolved to become an essential part of life for nearly every person on the planet. The 24 satellites that make up the GPS constellation freely provide positioning, timing, and navigational information worldwide–especially for the U.S. military. GPS allows units in the air, on land, and at sea to know their position at all times; quickly agree on a common, synchronized time; and navigate across unfamiliar terrain with relative ease.

The Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) and other weapons use GPS to achieve unparalleled accuracy. These weapons are capable of traveling for miles and landing within 10 feet of their targets.

The Pentagon’s reliance on GPS has made its disruption or destruction the number one priority by adversaries in wartime. Anti-satellite weapons, GPS jammers, and even GPS spoofers are designed to destroy, deny, or degrade the network, forcing U.S. and allied forces to rely on older, less accurate ways of determining their finding their way around.

Russia, China, and North Korea have all developed and deployed GPS countermeasures, some of which have interfered with civilian GPS usage. In 2019, pilots discovered Russian GPS jamming (to protect Moscow’s forces in Syria) interfering with civilian air traffic in the Eastern Mediterranean, from Cyprus to Israel.

The U.S. military has rolled out a number of alternatives to GPS, including navigating ships by sextant. One idea that seemingly holds a lot of promise: magnetic anomaly navigation techniques, or MAGNAV.

The magnetic field protecting Earth from solar winds is all encompassing, but varies by location. These variances, recorded by a magnetometer, can be correlated to a map of the planet. The result is a magnetic map of Earth that doesn’t require satellites or even a physical map.

MAGNAV, as Defense One points out, is accurate to within 10 meters (32 feet). That’s not as accurate as GPS, but it is much more accurate than other means, including older inertial navigation systems. MAGNAV doesn’t rely on a network of vulnerable satellites, and it’s extremely difficult to jam. It would take a nuclear explosion to “jam” Earth’s magnetic field and render it unreliable for navigation. That probably rules out MAGNAV as a means of fighting a nuclear war, but it would remain very useful in conventional conflicts.

The biggest problem with magnetic anomaly navigation is the system is useful for peacetime and navigating over friendly terrain, but it’s not clear how the U.S. military gets magnetic maps of potential adversaries. One possibility is that a MAGNAV-powered cruise missile might use magnetic field mapping to cross international waters and then switch to an inertial navigation system (INS) once in enemy territory. While not ideal, a reduction on reliance on INS would make for greater overall accuracy.

Kyle Mizokami,