The Terrible Honesty of World War III Memes

By Molly Roberts

There’s a war on. Or at least, there’s a war online.

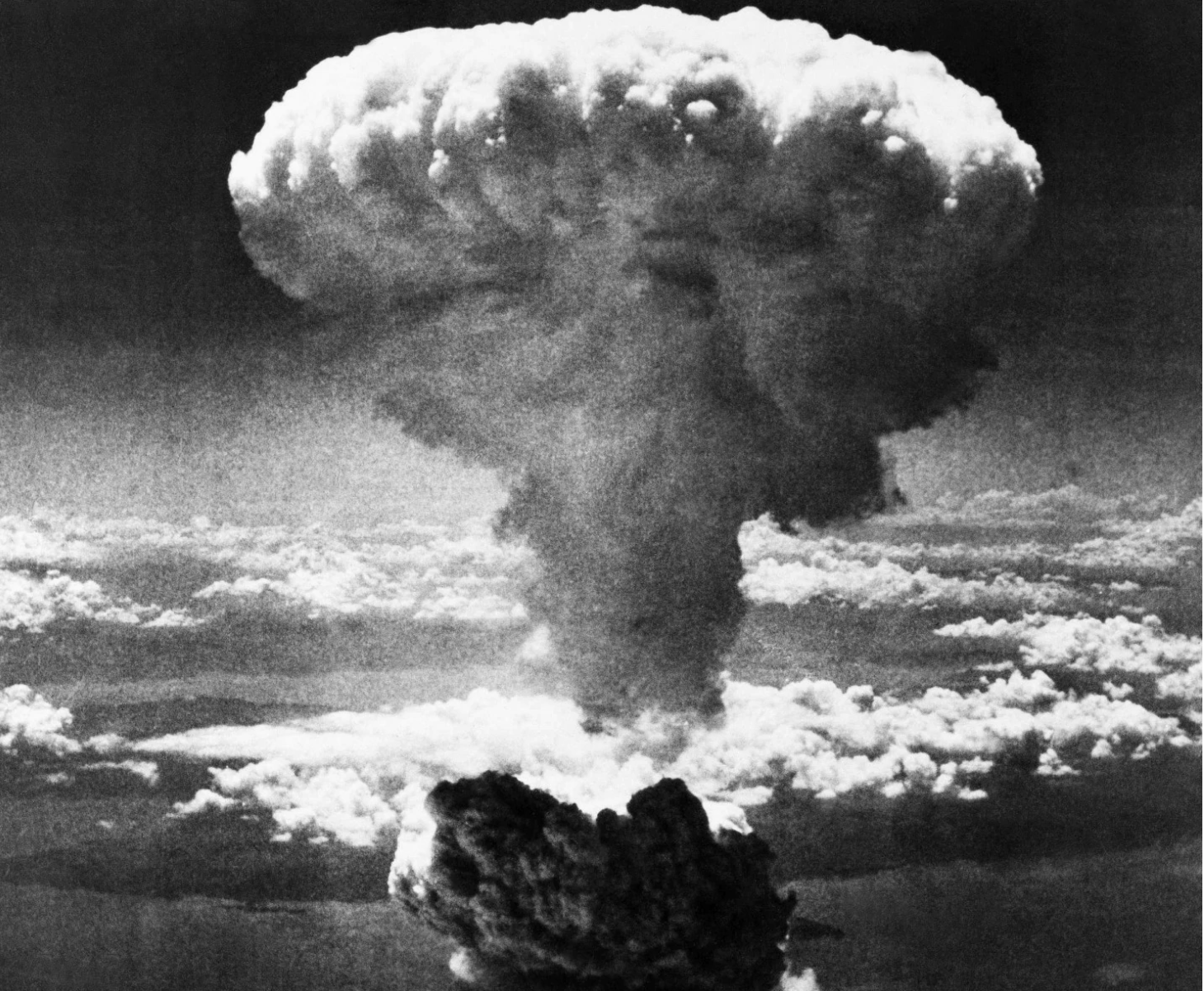

The inaugural meme of the dawning decade homes in on nothing less than the total annihilation of humanity. The mushroom clouds familiar to us from the pop canon loom over the Internet, and now they’re accompanied by image macros with captions about how last week’s U.S. airstrike that killed Iranian Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani will provoke global catastrophe.

Hashtag it World War III.

The kids are joking about what many adults have deemed unjokeable. The adults may think that meme-making, as we hover at the edge of disaster, displays the entitlement of coddled children who have never had to fight for much of anything at all, much less their lives. But if critics looked closer, they’d see a more honest treatment than many grown-ups are in the habit of providing.

The World War III memes are about how loony our predicament is, thanks in large part to the looniness of our president. For example: President Trump asks his iPhone to tell him how many miles he ran today. “Okay, sending missiles to iran today,” Siri replies.

The memes are also about how much damage, and how many casualties, that bizarre reality could cause. Will kids who have always lived against the backdrop of armed conflict suddenly find themselves on its front lines? There are posts about getting drafted and posts about making sure you don’t: “When the US government asks for my birth certificate,” reads the text of a tweet alongside a photograph of a fully grown man above which is written in green crayon “I am 12.”

Very often the memes are about video games: how they’ve pumped a rising demographic full of ideas about battle, and how quickly those ideas deflate when you prick them with the possibility of taking the bloodshed off-screen: “When I arrive to the battlefield and see no one respawning” is the context for a screen grab of a dopey Patrick from “SpongeBob SquarePants” superimposed with the words “Mom come pick me up I’m scared.”AD

The references to despair, draft-dodging and plain old terror betray a terrible self-awareness among these ostensibly glib teenagers: They weren’t made for war, because very few people are.

There’s no need for this generation to fake bravery where it doesn’t exist, or to rare for a fight that could lead to their own meaningless deaths and the meaningless deaths of countless Iranians and Iraqis. These kids grew up watching things fall apart overseas and never watching America succeed in putting them back together. No gauzy mythos fogs their eyes, so they can tell the truth about themselves and about this whole mess, and the truth is they’re afraid and the whole mess is crazy.

The truth is also, as it turns out, eminently memeable. Memes have always been a vehicle for nonsensicality and nihilism; a ground invasion in Iran both does not make sense and could prove so calamitous that in the end there might really be nothing.AD

The high-schoolers don’t even have to envision this atmosphere of utter destruction for themselves, because as with much of the cultural detritus that gets repurposed as memes today, it’s already in the air. The kind of conflict the United States invited last week has long been imagined by toy manufacturers, sci-fi writers, blockbuster bankrollers and, yes, video-game visionaries. The art of meme-making is to pick through an oversaturated information environment and stitch something together. In this case, that something is the apocalypse.

And why not? What’s art for TikTokkers and Redditors and tweeters imitates what life feels like for them, and life over the past three or four years has felt like an ambient catastrophe. We have a simmering sense that something is always somewhat wrong, every day, even when the CNN chyron isn’t displaying a threat of fire and fury or immigrants in cages. Now, finally, there’s a way to distill this emotion into a ready-made tableau: bullets everywhere until an atomic bomb arrives to blow it all away.

The channeling of anxiety into a single, simple and digestible format — an enduring symbol for the moment — might be familiar to baby boomers as a postage stamp; for late Gen-Xers or early millennials, an emoji. But for the youth of today, it’s a meme.AD

This, in 2020, is the way the world ends. Not with a bang, but with SpongeBob holding the nuclear football.